Books, an immutable double-entry accounting database service

Tracking financial transactions at scale

Square in 2019 looks very different from when we launched almost 10 years ago. We now have at least half a dozen totally independent products, from Caviar, Capital, to the Cash App. As we have scaled our financial infrastructure and moved beyond simple payment processing, we have come to recognize our need for strong foundational technology to support our efforts.

As we added new products, our settlement services - the part of the tech stack responsible for determining how much to pay to our merchants each night or via Instant Deposit - became increasingly complex. While it excels at simple payment processing needs, it strained under the weight of increasingly complicated products. Additionally, we occasionally observed inconsistencies in the data, resulting in customer inquiries and delayed deposits.

We decided to invest in a scalable database technology intended specifically for tracking financial transactions. We wanted to provide infrastructure which ensures that every dollar, euro, or pound we move is accounted for, and we wanted to ensure that we could scale to meet the needs of our increasingly diverse product suite without putting a burden on our product engineers to build this functionality themselves in their products.

Over the last year, we built a new kind of database, called Books, and adapted our payments infrastructure to use it. We designed Books to support many clients and businesses at global scale, leaning on Google Cloud Spanner and Google Kubernetes Engine to make that possible. The data model is inherently consistent as a result of directly applying Double Entry Accounting.

Problem

Our original settlement service started fairly simple - it had tables for accounting adjustments and would run through marking each with a payout identifier when it had been settled.

Over time, this strategy stopped scaling with our payments business.

- At the moment, when you want to trigger a bank settlement, you have to calculate the balance for a merchant. This requires doing an expensive group-by aggregate for each merchant, storing that balance, and executing the ACH transfer in a timely fashion. This really struggles if you have to pay out millions of payments on a daily basis. What’s more, we now have products (like Square Capital) that will create O(# payments) additional entries depending on whether the merchants are also on a Capital loan.

- It’s impossible to split a single payment into multiple payouts, since there is a many-to-one relationship of payments to payouts. This makes for frustrating product limitations - if a merchant we deem risky makes a single $100,000 transaction, we have to decide to block the entire transaction or none of it.

- Since this is just a SQL database, there’s nothing preventing the payouts from becoming inconsistent. The payout_id can be ensured to be a valid foreign key, but nothing is stopping it from being nulled out.

Add on to this all the normal issues that come with a growing business. We spent considerable effort adding a sharding scheme to the SQL database. We built a risk model on top of the ledger to mark certain entries as “unsettleable”, creating a weird wart on the system. And eventually we had to deal with cross-shard transactions, where two different merchants could exchange value. All the while, this database remained more or less unprotected from accidental corruption.

So after maintaining our old ledger technology for years, we decided to build a new kind of database that solves these problems fundamentally, for us or any other customers at Square (or beyond).

Solution

The Books service offers the following properties:

- Flexibility - it needs to be able to scale to an arbitrarily complicated business model and relationship between customers and Square.

- Consistency - the financial data has to be consistent, that is - you should never be able to transact with the database in a way that results in an illogical financial transaction. “$100 of paid-out ledger entries but $50 of payouts” should be impossible.

- Scale - it must support massive scale in terms of individual account size (throughput) and total data stored.

Double Entry Accounting Primitive

To address consistency, we picked a well-established, public-domain, battle-tested approach to modeling financials that enables all of our properties: Double Entry Accounting.

Double Entry Accounting forces you to state not just what financial state change occurred, but why. The accounting equation states that all transactions (which we call “journal entries”) must balance to 0, so each cent lost is matched with a cent gained.

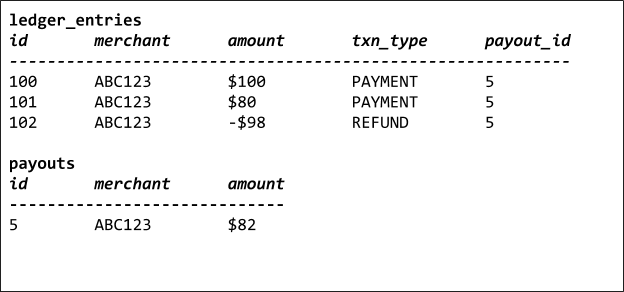

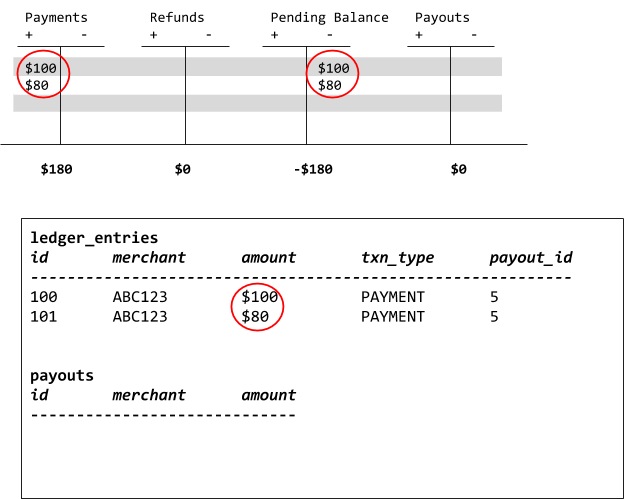

Here is our revised accounting representation of our relational data:

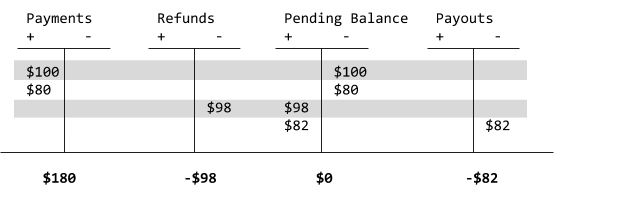

There’s a bit to unpack here, so let’s break down what this diagram represents in terms of our mysql data. Before we do that, we need to talk about what a book is. In the above diagram, we have four different books, called “Payments”, “Refunds”, “Pending Balance” and “Payouts”. Think of these as states in a state machine and we’re moving pennies between these states in bulk. Each book holds a balance, essentially summing up all of the changes to that book. Books are immutable and can only have the balance changed by participating in accounting transaction.

Now that we can explain what a book is, we can dive into our example data, in which we have two payments we have to resolve:

These payments are now recorded as two different journal entries that debit (the plus sign) our Payments book by $100 and $80 respectively. To offset these and ensure our accounting equation balances, we credit (the minus sign) our Pending Balance book. After these two payments, the balance on the Payments book is $180. The balance on our Pending Balance book is -$180.

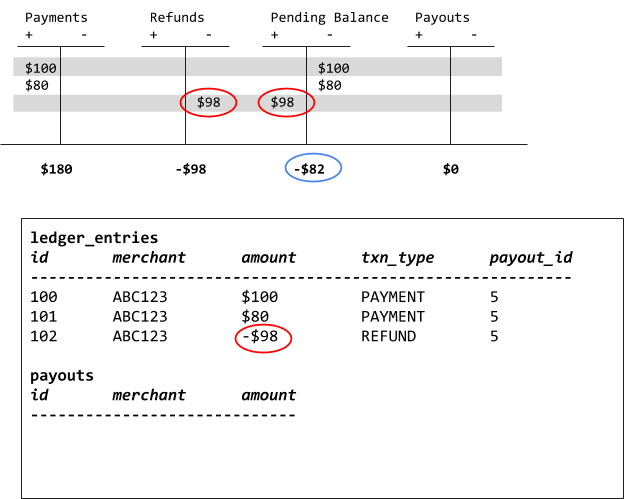

The next thing we want to record is the refund. Our Refunds book is going to be credited (again, the minus sign) the amount of the refund and we will debit the Pending book.

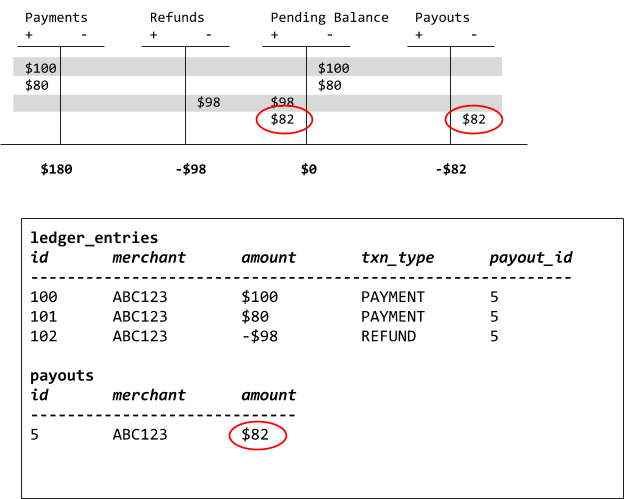

At this point we now have both payments and one refund booked. We would now like to resolve the day’s transactions and pay the merchant anything we owe. Conveniently, though not coincidentally, our Pending Balance book has provided the exact number for us to use for our final journal entry, the payout.

Unlike before, the calculation of how much to pay out for this merchant is a single row in our database and requires no complex grouping or aggregation to determine. It also means we can split our payouts by arbitrary amounts instead of being forced to operate in terms of the entries we already have.

One common thing engineers trip up on early is the meaning of the signage. What does it mean for the Pending Balance book to be negative $82? The best way to think of Double Entry Accounting is as describing the value the entity keeping the books (in this case, Square) has. The more positive, the more valuable Square’s assets are. The more negative, the more value Square owes or has lost. This is probably the least intuitive thing about accounting and it took us some time and a series of exercises and some practice for it to click. In fact, for the ease of modeling we relaxed how we reason about it and we don’t stick to standard Double Entry Accounting which has debit-normal and credit normal books which determine the sign as we prefer to consistently treating debits as positive and credits and negative.

Modeling Double Entry Accounting in SQL

Armed with a primitive that is very flexible and provides consistency, we now needed to model it on top of some sort of storage system.

To meet the scalability requirements we picked Google Cloud Spanner. It is a fully managed, globally distributed SQL database which let us not worry about sharding and the maintenance burden of running a database.

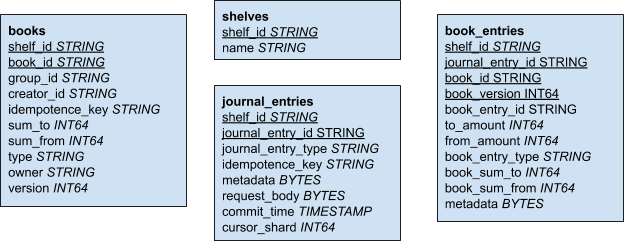

This is a diagram of simplified schema version that our service uses:

At a high level, the schema for a Double Entry Accounting database is extremely simple. There are three high-level tables required to form an accounting system:

- books: this table has one row for each book, as used in the example above. It holds a balance, can have a type, owner, and a unique identifier.

- journal_entries: every time our books change value in an accounting transaction, one row is added to this table.

- book_entries: each row in this table has foreign keys to both a journal_entry row and a book row. A book entry holds either a debit (+) amount or a credit (-) amount. Additionally, we keep a monotonic counter for each book reflecting its current version. For a book that has participated exactly once in 50 journal entries, we expect its version number to be 50. The same book can appear multiple times in the same journal entry.

In order to make our Books API as useful and powerful as possible, we needed to add a few more concepts to enable it for Square-scale usage.

- Multitenancy: We anticipated that there would be substantial value in allowing multiple internal clients at Square use this system without having to reinvent it themselves. Books models a tenant as a concept called a “shelf”. A huge challenge for our multitenant setup is ensuring that these different services don’t clobber each others’ workloads. For that reason, all the secondary indices in Books that can be influenced by user data are namespaced by the user’s shelf. For example, the index that lets us query all books by a particular owner is the tuple (

shelf_id,owner,book_id). - Horizontal scalability: Even though Spanner sells a promise of delivering horizontal scalability transparently, in order to achieve it the schema has to comply to few core rules. For starters, monotonically increasing integers had to be replaced with UUIDS. To run queries against timestamp-ordered data, the schema had to be carefully designed to avoid hotspots (see

journal_entrytable andcursor_shard+commit_timestampfields in the database schema). Lastly, we had to make sure that we’re correctly co-locating data using by interleaving tables (the book entries are interleaved with journal entries). These and a few other things that we had to take into account are very nicely documented in the official documentation, yet it took us some time and experimentation to get it right. After some trial and error and testing it under load we got it right and were able to scale horizontally by simply adding a few new nodes in the Spanner console.

Immutability

After explaining the basic concepts of Double Entry Accounting and how we implemented it on top of SQL database it may be apparent to you that the Double Entry Accounting primitive imposes one other feature - immutability.

Because we cache balances on the book_entires, both journal and book entries data sets are effectively append-only and immutable once stored. This is a very powerful property of the system which can be viewed as an audit log of all operations that have ever happened.

But you may ask: What if a bug is deployed, and we journal money movements that are not correct?

You can’t update the data in place. In fact, besides the books table which is inherently mutable (current balance is updated on every operation) there are no update statements for the tables presented on the diagram, only inserts. This means that if you make a mistake what you want to do instead of updating is to write a new entry that corrects the previous one. The balance of a given book will be adjusted but there will always be a trace of what happened in the system, even if it happened by mistake but this is not a bug - this is a feature.

Summary

Introduction of Books at Square has a big success and has already provided a lot of benefits. Thanks to Double Entry Accounting we’ve discovered a lot of improvements we could make to our existing, single entry data. On the infrastructure side, thanks to Spanner we don’t have to worry about application level sharding and together with Kubernetes we have a very elastic, horizontally scalable service. At the time of writing this blog post, the service is managing ~20TB of data and is developed and maintained by a small team of three people.

If you’re interested in working on payments infrastructure and services like Books, consider joining us!