Caviar iOS: Migrating from AdvancedCollectionView to PJFDataSource

Behind-the-scenes look at the evolution of PJFDataSource in our Caviar iOS app.

Written by Michael Thole.

In December 2014, we released the first version of our iOS app for Caviar, our high quality restaurant delivery service. The view controller architecture of the app was largely based on the framework laid out in Apple’s 2014 WWDC Talk: Advanced User Interfaces with Collection Views and accompanying sample code. This was a good starting point for our app, but we eventually became frustrated with it for reasons I’ll detail below.

After considering multiple approaches, we decided to build a small library reimplementing the functionality of AdvancedCollectionView that we valued the most, while leaving out any complexity we didn’t need. To push us towards building a generally useful library that’s not tied too closely to the Caviar app, we built this from the beginning as an external library. We’ve been successfully using it for over 6 months now and have decided to to open-source it to the public as PJFDataSource.

In this post, we’ll look at the creation of PJFDataSource as it evolved: as a replacement for the AdvancedCollectionView sample code in our early app architecture. If you’d rather just dive in, head over to our GitHub page.

A Good Starting Point

Basing Caviar’s iOS app architecture off of Apple’s AdvancedCollectionView sample code was a great starting point, despite the issues we eventually encountered. It provided a consistent approach for loading data and display content throughout the app, and pushed us towards many best practices.

Most importantly, AdvancedCollectionView helped us avoid creating Massive View Controllers, a common iOS app architecture pitfall (for which there are many goodsolutions). It did so primarily by requiring each piece of content to have a data source object, separate from the view controller itself. These data source objects are the model for your content view. In this implementation these objects are also responsible for loading their content — another responsibility that might end up in the view controller with a less disciplined approach.

These data sources can even be composed together like building blocks into an “aggregate data source”, encouraging the creation of smaller component data sources. This allowed for code reuse for identical components in different parts of the app. For example, the list of food items you’ve added to your cart and the list of food items on a historical receipt could share one of these components data sources, as they’re representing the same content, just in different contexts.

AdvancedCollectionView also provided a consistent approach to displaying loading, no-content, and error states. It did so by tightly coupling the data source object with the UICollectionView displaying your content, adding supplementary placeholder views when appropriate. While non-obvious at first, this became one of our favorite “features” of AdvancedCollectionView and played a large part in the shaping of PJFDataSource.

Problems… and Solutions

As we moved past the initial release of Caviar for iOS and began to settle into a regular feature-building and bug-fixing release cycle, we began to recognize some drawbacks to using the AdvancedCollectionView as heavily as we did. These are all interrelated, but I’ll discuss them around the themes of flexibility, stability, and community.

Flexibility

As you may have guessed from the name, AdvancedCollectionView requires the use of a UICollectionView. You’ve probably heard the adage “if all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail”. For us, UICollectionView was our hammer, even though it wasn’t always the tool best suited for the job. This lack of flexibility hit us in several ways.

A simple, concrete example comes from the Home screen, where Caviar lists all of the restaurants you can order from. In our larger markets, this can be hundreds of restaurants, each with a variable-height cell depending on the associated metadata. Traditionally, collection views and table views need to determine the size of every cell in order to calculate its own content size. With a lot of content, this can be slow and negatively impact the user experience. For UITableViews, Apple added tableView:estimatedHeightForRowAtIndexPath:, an elegant solution for this issue. Without access to something similar in our collection view layout at the time, we were forced to implement our own fast view sizing and caching — complexity we would have preferred to avoid.

More generally, using UICollectionViews nearly everywhere in the Caviar app was simply overkill. Almost all of the screens could be implemented more simply using a UITableView. Some could even be implemented with a UIStackView-based layout (with OAStackView for iOS 8 compatibility), or even with manual UIView-based layout.

This experience was the main reason we decided that PJFDataSource should be view agnostic, leaving it up to the app to provide its own content view. Rather than being tightly coupled with the collection view, PJFDataSource provides a “content wrapper view”, which will display either the content view you’ve provided, or one of the various placeholders for handling loading, no-content, and error states.

In the Caviar app today, we try to use the tool that fits best. The Home screen is now a UITableView, taking advantage of automatic cell sizing and using estimated heights for speed. The Menu view, where we show mouth-watering photos of all the food available at a restaurant in a waterfall layout uses a UICollectionVIew. The Account view, with its limited content, uses a UIStackView — one of my current favorite tools.

Stability

Once the Caviar app was publicly released and being used by orders of magnitude more customers than our internal test group, we found that a few of those mysterious “one off” crashes weren’t “one off” at all. Instead, they were early warnings signs of crashing bugs somewhere in our data source stack.

Once we realized this, we dug in deep to find and fix the underlying issues. We set a target of 99.9% crash free users, as measured by Crashlytics. We added Crashlytics logging to support better forensic investigation after a crash in the wild. We wrote automated tests to stress-test problematic areas. We learned a lot about common bugs and/or misuses of UICollectionView. We fixed several issues, making a dent in our crash rate. But we couldn’t figure out all the issues, and we couldn’t quite get the crash rate down to our target.

These mysterious crashers were a major driver in our decision to ultimately abandon AdvancedCollectionView and create PJFDataSource. We made hitting our crash rate target the primary goal of the migration. We staged our engineering and rollout incrementally, prioritizing the pieces of the app most affected by these crashes.

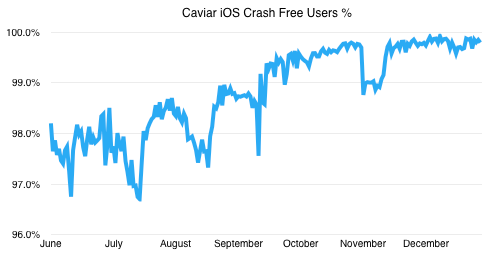

Let’s look at some real numbers from the last half of 2015 for context:

As you can see, we started with crash-free users rate of about 97.5%. This means that a customer using our app had about a 2.5% of seeing a crash on any given day. Ouch.

We made some incremental improvements (and regressions) throughout the first couple months. In our mid-September update, we shipped the first version with a partially rolled-out PJFDataSource. We see a great improvement right off the bat, and then continue to improve as we update more portions of the app and our customers upgrade to the latest version. In the last ~6 weeks of the year, we manage to finally hit our 99.9% crash free target, which we continue to maintain today.

I strongly recommend setting an aggressive target like this for your crash-rate, and quickly fixing any regressions that cause you to dip below. This ensures a strong signal-to-noise ratio in your crash reporting, making regressions easy to spot and fix. It also helps you notice the crashes faster, while the recently-changed code is still fresh in your mind.

Community

In retrospect, one issue with AdvancedCollectionView that we initially underestimated was the lack of community support for it. There wasn’t a canonical home for it on GitHub where you could interact with the authors or other users. There wasn’t anyone planning to fix bugs. There wasn’t anyone making compatibility fixes when a new version of iOS or Xcode came out. There weren’t any experts for us to lean on when we hit a wall.

All of this was clear from the beginning, and is inherent in taking a 6,000 line sample project from WWDC and building on it — we just underestimated the long-term cost. This experience made me better appreciate the many vibrant communities that exist throughout the iOS ecosystem.

Incremental Change

It’s worth reiterating how incremental this change was, as I think it’s a good example of how to consider and execute major architectural changes in a shipping app:

1. Identify the issues

-

For us, the two major issues were the crashers and the inflexibility/complexity from using UICollectionViews essentially everywhere.

-

There were also concerns about long-term ownership of the AdvancedCollectionView, but we could’ve solved that by biting the bullet and really “owning” it ourselves.

-

We also identified the pieces that we really liked and would want to carryover to any potential replacement.

2. Look for smaller changes to address

- We spent a considerable amount of calendar time trying to find the silver bullet or two that would fix the major crashes. Only after having found multiple issues, making fixes, and seeing only incremental improvements did we decide this was potentially worthy of a larger architectural change.

3. Come up with a plan and goals

-

Very early on, we established our 99.9% crash-free user goal.

-

More loosely, we also knew we wanted to allow greater flexibility in choice of content view, especially as iOS evolves and new tools are added (e.g. UIStackView).

4. Incrementally engineer and rollout

-

We could have focused exclusively on this for a period of time, rewrote all the view controllers in the app, and shipped it in one big bang. Maybe it would’ve worked, but more likely we’d have missed something and caused some major regressions along the way.

-

Instead, we methodically migrated towards PJFDataSource on a screen-by-screen basis (ordered by expected impact). We regularly shipped to our customers, found minor issues, and made refinements along the way. Because this was a “slow burn” type of project, we were able to continue making progress on new features and fixing minor bugs in other areas at the same time.

5. Evaluate

- Increased stability, increased flexibility, reduced complexity. Success!

Conclusion

Hopefully this backstory on the creation and evolution of PJFDataSource will be of some use to you next time you’re evaluating a potential dependency or considering a significant refactoring.

If it looks like something you might want to use yourself, head over to our GitHub page.

Square’s iOS engineering team invites you to join us for an evening of lightning talks, plus food and drinks with your fellow iOS engineers during WWDC. Join us at The Box SF on Tuesday, June 14th — doors will open at 5:30pm. RSVP here to reserve your spot! Michael Thole - Profile *Engineering Manager @ Square. Previously . I love building products of consequence.*medium.com